I cannot remember when I first heard of Elizabeth Hardwick - it must have been in relation to her essay collection Seduction and Betrayal (1974) - but it wasn't until 2018 that I read her work. Last year I was excited about the publication of The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979, a collection of letters exchanged between Hardwick and her ex, poet Robert Lowell (d. 1977), and their friends. To give you a little backstory: The title refers to Lowell's poem collection that earned him his second Pulitzer Prize in 1974. What made it controversial was that Lowell not only used Hardwick's letters, written to him in a state of emotional distress, but also changed them to fit his narrative. I thought it would take a few weeks to read through 500 pages of correspondence but found myself unable to put the book down and finished it in a few days. When I was done I went back to page 1 and started all over again, reading one or two letters before bedtime.

№ 23 reading list:

1 Sleepless Nights · Elizabeth Hardwick

2 The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979: Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert

4 A Tale of Love and Darkness · Amos Oz

5 Mislæg gatnamót · Þórdís Gísladóttir [Icelandic poetry]

6 To Kill a Mockingbird · Harper Lee [rereading]

7 Museums as Cultures of Copies edited by Brita Brenna, Hans

1 Sleepless Nights · Elizabeth Hardwick

2 The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979: Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert

Lowell, and Their Circle edited by Saskia Hamilton

3 How to Write an Autobiographical Novel · Alexander Chee4 A Tale of Love and Darkness · Amos Oz

5 Mislæg gatnamót · Þórdís Gísladóttir [Icelandic poetry]

6 To Kill a Mockingbird · Harper Lee [rereading]

7 Museums as Cultures of Copies edited by Brita Brenna, Hans

Dam Christensen and Olav Hamran

Translated by: 4) A Tale of Love and Darkness: Nicholas de Lange

I would like to thank Routledge for the museum studies textbook on the list, which consists of 17 chapters by leading scholars in the field. It will enable me to keep up with my studies this summer without any deadlines.

Back to The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979: If you already know the backstory and are intrigued then you may want to watch writer and critic Hilton Als in conversation with Saskia Hamilton, who edited the letter collection and added useful footnotes. What made this event even more memorable is actress Kathleen Chalfant's citation of three letters by Hardwick. In my copy I have marked many sections, one where Hardwick describes a certain mood in a letter to Lowell on January 13, 1976, when they were back on friendly terms:

Back to The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979: If you already know the backstory and are intrigued then you may want to watch writer and critic Hilton Als in conversation with Saskia Hamilton, who edited the letter collection and added useful footnotes. What made this event even more memorable is actress Kathleen Chalfant's citation of three letters by Hardwick. In my copy I have marked many sections, one where Hardwick describes a certain mood in a letter to Lowell on January 13, 1976, when they were back on friendly terms:

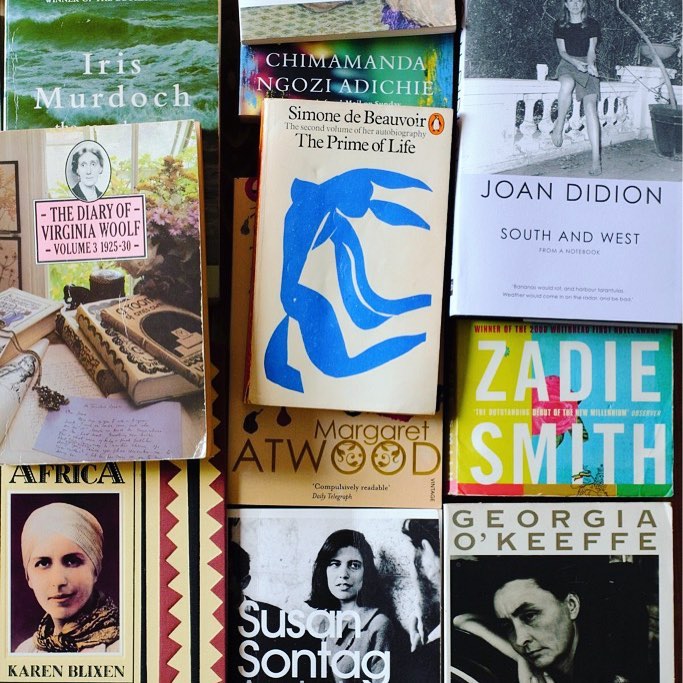

... and strangely enough I do feel like writing just now and have fallen into a mood of reading books, thinking, idling about–all that puts one into the frame that makes writing possible and the life of literature beautiful and thrilling.On the reading list is also Hardwick's Sleepless Nights (1979), a slim novel, partly autofiction, which I have also finished. I think I benefited from reading it after her personal letters, in which one learns about its writing process.